Burrowing sea cucumber

(Cucumaria miniata) As their name suggests, the burrowing sea cucumber keeps most of its body tucked under the sand or rocks. Their feather-like oral tentacles are often their only visible body part. Take a close look and you just might see them slowly eating, bringing in one oral tentacle at a time to their mouth in the center. Almost like licking your fingers after a good meal!

Painted anemone

(Urticina crassicornis) Also known as the Christmas anemone, the painted anemone is common throughout the intertidal zone (the area where the ocean meets the land between low and high tides). The banding acorss their tentacles can help to identify this tide pool regular, as you may find them in a variety of colors. The opening in the center of their tentacles is the anemone’s mouth. They use their tentacles to capture small prey like crabs or shrimp.

Take a peek under the waves!

Experience the outer coast of Washington state—with its towering rocks, big waves and lots of life—right here inside the Seattle Aquarium.

Notice the wave action: It brings food, nutrients and oxygen to the habitat. But those waves also mean that animals living here have to be ready for anything that comes their way.

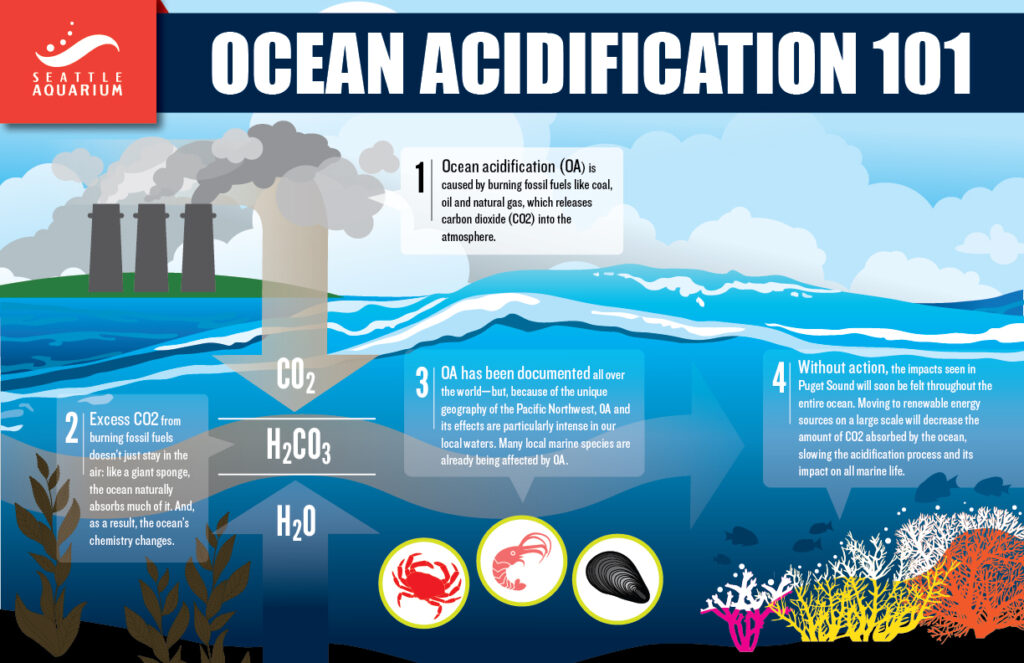

The ocean acts like a sponge, absorbing excess carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere—which changes its chemistry. Animals like snails, urchins and crabs use minerals from the water to build a strong shell. When the water chemistry changes, there are fewer building blocks for these animals to use in making their homes.

When we reduce the CO2 we create—our carbon footprint—we’re helping the health of our ocean. And there are many ways to do that, such as taking the bus or riding your bike instead of using your car and supporting renewable energy when you can. Even leaving shells at the beach can help! Shells break down over time and put those building blocks back in the water for another animal to use.

Isn’t that just a rock?

It may not be obvious that some of the animals here are indeed animals! But they are. They have homes, they travel and they have to find their dinner.

For instance, did you know that barnacles cement their “head” to the rock and eat with their “feet”? Inside that hard exterior, the barnacle is doing a headstand and using feathered appendages called cirri to capture a delicious dinner of plankton. Snails build and carry their shell home with them wherever they go. When it’s time for dinner, they use a specialized tongue called a radula to scrape algae off the rocks. Sea urchins and sea cucumbers have appendages called tube feet that help them to sense their environment. It would be like being able to taste everything you touched with your fingers and toes!